Our final post for "Battle Robots of the Blood"!

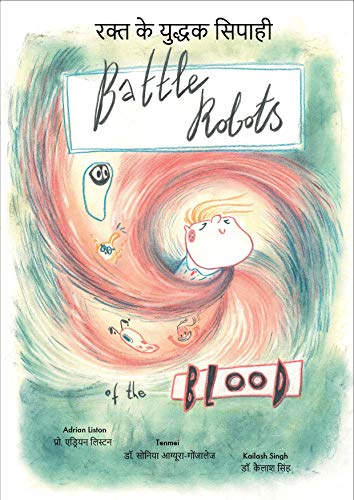

Follow the story of Tim, a seven year old who lives a slightly different life to the majority of us. After being introduced to different aspects of Tim’s life, we find out that he has a primary immune deficiency disorder, which means that his immune system can’t protect him against attack from the bacteria and viruses that cause disease. This puts him in in grave danger, especially when exposed to diseases that people could be protected against by vaccination. The story is told in an engaging and light-hearted manner, but still carries the message that vaccination is important for everyone and protects the most vulnerable. The story is beautifully illustrated by Dr Sonia Agüera-Gonzales (Tenmei).

The paperback is appropriate for children 5 to 12 years of age, and is available through Amazon in the US and UK. The English version is available in Kindle stores worldwide, including US, UK and Australia. The associated activity book is free to download here.

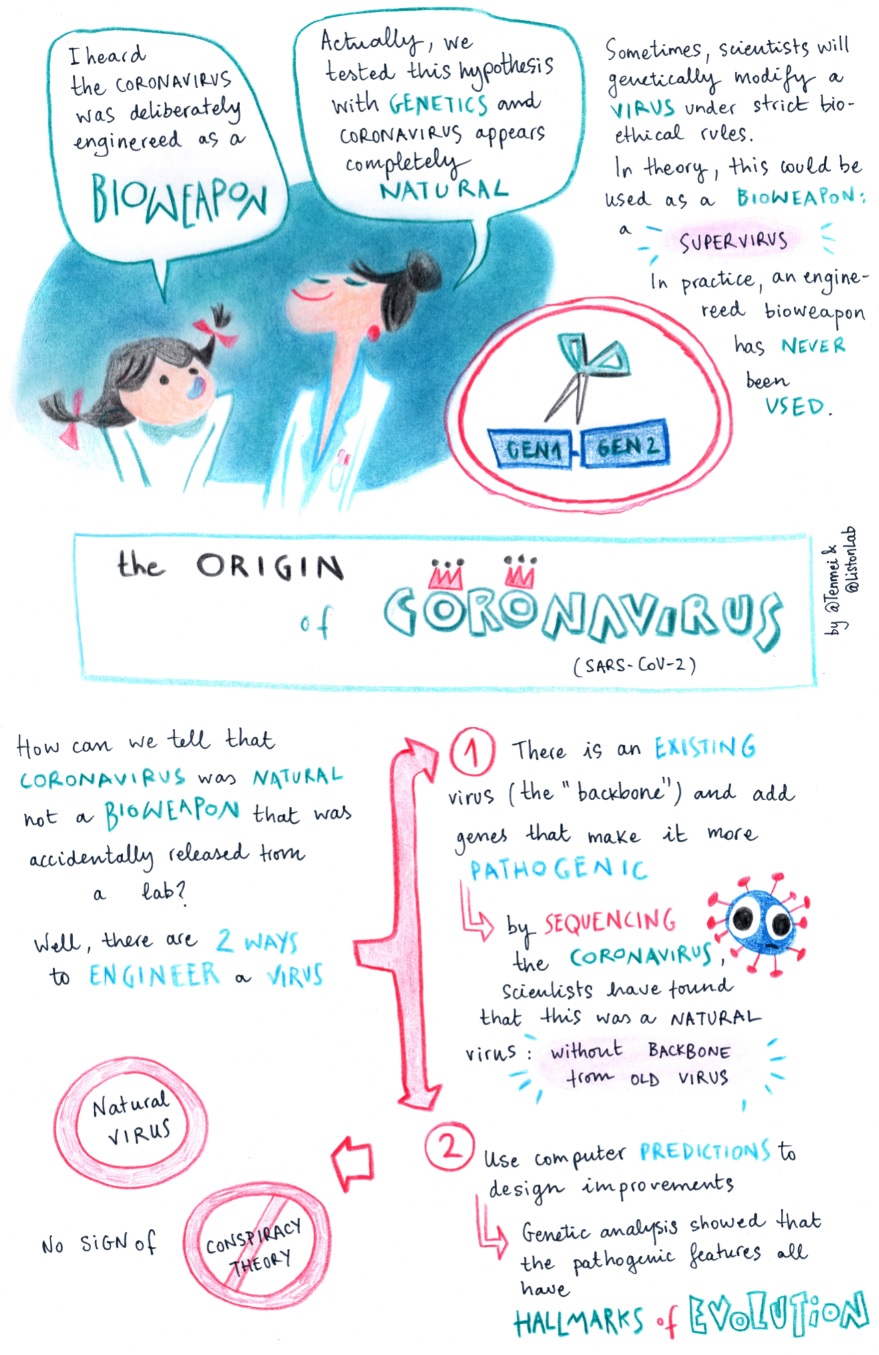

The Coronavirus pandemic teaches us that viruses don’t respect borders or linguistic barriers. For vaccination to be truly effective at protecting vulnerable people like Tim, we need to have almost everyone else in the community vaccinated. As scientists we have been historically poor at reaching out to the immigrant component of our communities, and this is reflected by lower vaccination rates. We have therefore embraced the linguistic skills of our international laboratory to translate the book into ten additional languages.

To download the eBook in other languages:

Try French, translated by Prof Stephanie Humblet-Baron, lead of the human immunology team in Leuven.

In Dutch and German, written by PhD students Mathijs Willemsen and Julika Neumann, working in the human immunology team.

In Portuguese, translated by Dr Lidia Yshii, lead of the neuroimmunology team in Leuven. In Spanish, translated by Dr Carlos Roca, head of data science in the Babraham team

In Czech, written by Dr Alena Moudra, in Urdu, written by Dr Samar Tareen, and in Hindi, written by Dr Kailash Singh, all post-docs in the Babraham team. In Polish, written by Urszula Karpinska, from the animal research centre in Babraham, and in Chinese (simplified) and Chinese (traditional).

Thursday, April 23, 2020 at 6:49PM

Thursday, April 23, 2020 at 6:49PM

Coronvavirus,

Coronvavirus,  genetics,

genetics,  science communication

science communication