In his laboratory at the University of Cambridge, immunologist Adrian Liston studies the complex inner workings of the immune system with a focus on regulatory T cells that help keep the body’s immune response in check. But beyond the bench, he whittles down the jargon-filled, methodical, and nuanced research and transforms it into digestible nuggets of scientific communication for young audiences.

“Kids are naturally curious about how the world works,” said Liston. “They will quite happily learn about how anything works so I don't think there are topics that are out of bounds in terms of science.”

Liston’s own journey into science communication for children and teenagers is inspired and influenced by his personal experience. “As [my son] has developed, I've developed as a father, and I've used what I've learned as a dad to keep pace in my public communication efforts,” said Liston. From children’s books to a computer game to a graphic novel, Liston has altered the medium, language, and message to evolve with the next generation’s shifting interests.

Drop the Jargon, Focus on the Message

As a young child, when Liston’s son asked him about his work, Liston, “learned to talk in his language.” Scientists spend decades learning a precise language, chock full of scientific terminology and tongue-twisting acronyms, that allows them to succinctly and accurately communicate their findings to peers. But when it comes to communicating research to nonspecialists, regardless of age, Liston finds it important to keep it high level.

“Sometimes people get so hooked on trying to communicate the details that the concept doesn't come across.” Liston cuts out the jargon to spin a narrative that is accessible and resonates with the intended audience.

In Liston’s children’s book Maya’s Marvellous Medicine, the title-character learns about how vaccines help prepare the cells in the immune system for battle.

For instance, he used this technique in his children’s book Maya’s Marvellous Medicine, which follows the young title character as she learns about vaccines and how they boost the immune system. Instead of going into the specifics of vaccines, Liston focuses on a simple concept that is accessible to young children: practice makes perfect. Maya’s father uses a relatable anecdote from Maya's life—when she won a running race after lots of practice—to lay the foundations upon which her doctor explains how the immune cells in our body learn to recognize the microbes that cause diseases.

When writing books for young children, Liston targets two diverse audience categories. “The ideal situation of a kid's book is when you're hitting the kids at one level, and the parents at another level.”

That’s why in his book Battle Robots of the Blood, he narrated the story from the perspective of Tim, a seven-year-old boy who has a primary immunodeficiency that renders him incapable of receiving life-saving vaccines.2 Frequent trips to the hospital are a part of his life, but wrapped up in the innocence of youth, Tim is preoccupied with spending time with his friends. However, this activity carries considerable risk for him, especially when his friends are unvaccinated.

The message to children is simple and clear: not everyone has a functioning immune system, so others need to get the vaccines that help to train the cool battle robots in the blood that fight against dangerous viruses. The message to the individual reading the book—often a parent or guardian—is also straightforward: getting their child vaccinated not only protects them, but it contributes to a herd immunity that helps save the lives of children who are unable to receive this marvelous medicine.

In Battle Robots of the Blood, Liston explores the life of Tim, a seven-year-old boy with an immune deficiency that leaves him vulnerable to a breakdown in herd immunity. “The idea is to try to create that empathy of the parents with the idea of a child being so sick that they could almost die, because someone else refused to vaccinate [their child],” said Liston. “If the person reading the book suddenly realizes for the first time that they have the ability to save other children's lives just by vaccinating their own child, then that's the epiphany we want them to have.”

Evolving the Medium to Match and Expand the Audience

As his son grew up, Liston saw an opportunity to learn about communicating with a new audience: teenagers. “I saw how engaged and focused he could be on computer games,” said Liston. “He could absorb information so well through that medium.” This inspired Liston to attempt science communication using video games. He teamed up with computer programmers to create Virus Fighter, a game that teaches people about the science of virology and the impact of vaccinations.

Players can choose to infect a population with one of four viruses—coronavirus, influenza, measles, or Ebola—and adjust settings that affect the virus's lethality, virulence, and incubation time to see how these properties influence viral spread. By introducing countermeasures, such as vaccinations, quarantines, and social distancing, the player can track how tweaks to these responses impact outbreaks, the health system, and the economy. Depending on the selected mode and settings, the game reveals different lessons. For example, Liston noted, “It's not just about how lethal a virus is, it's about how fast it spreads.”

In the computer game Virus Fighter, users play the role of Prime Minister of the UK as they make decisions to control the spread of a virus. The goal of the educational tool is to teach players about viruses, immunity, and vaccinations.

An added benefit of an online educational tool like Virus Fighter is that it expands the reach of science communication initiatives. Liston said that most science outreach initiatives are proximity-based; children living closer to a university are saturated with engagement opportunities, while children living further away, in what he refers to as ‘outreach deserts,’ are on the outskirts of the sci-comm ecosystem. “We need to make more content that can be decentralized,” said Liston. “The pandemic and the lockdown did demonstrate that we can do this, we can have innovative outreach mechanisms that are not grounded in geography.”

Science is Open to All

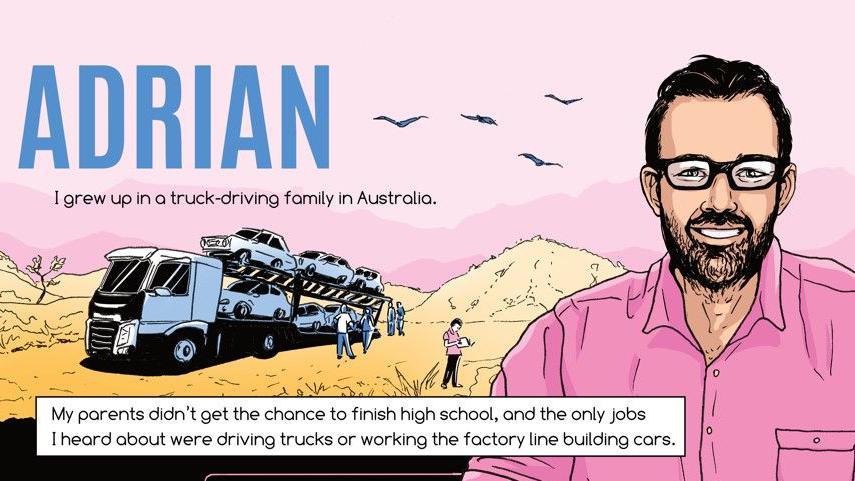

Throughout his career, Liston has been motivated by the inequities that exist in science and its communication. Growing up in a working-class neighborhood in Australia, Liston never had an opportunity to meet a scientist. “Science was something that was occasionally on the TV, but it wasn't something that I was ever able to encounter,” said Liston.

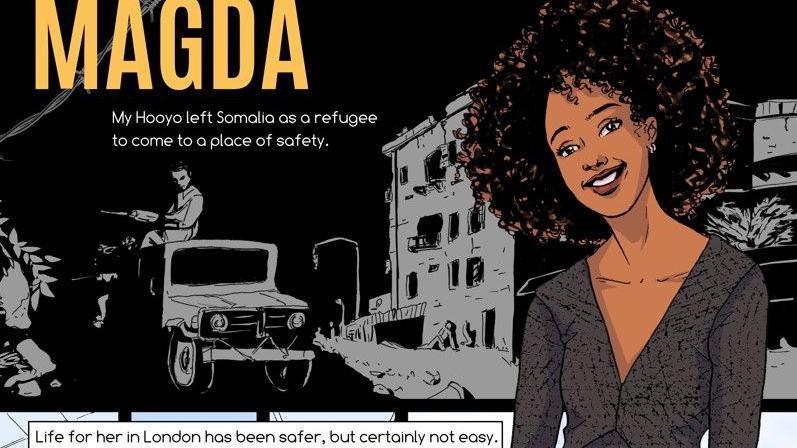

As his son entered high school, Liston embarked on a new project targeted at teenagers. Using comic art as his medium, Liston imparted a message that is near and dear to him: science is for everyone. “This project is not really about science, it's about being a scientist,” said Liston. His latest book, Becoming a Scientist: The Graphic Novel, includes 12 vignettes that highlight the varied backgrounds, role models, and motivations of scientists in his research team. Although everyone has a different story, they share a resilience, determination, and a sense of wonder that fuels their journey through science.

Liston hopes that his latest project, Becoming a Scientist: The Graphic Novel, inspires younger generations to pursue a career in science. “The idea was to just create a comic book where kids are going to flick through and see themselves in one person,” said Liston. “As soon as you see yourself in one person who is a successful scientist in Cambridge, you realize that this could be you as well.”

An abiding philosophy that shapes Liston’s day to day is that science is for everyone. “If science is for everyone, then science communication has to be for everyone,” said Liston. The more stories that get told, the broader the population that gets served. “No matter how good someone is at science communication, they can't do it for everyone, because different segments of the population are going to resonate with different messages and with different messengers,” said Liston.

To bring these important scientific messages and ideas to life, Liston collaborated with the artists Sonia Agüera-González and Yulia Lapko, software developers, and members of his research team—a reminder that good communication, like successful science, often results from the coming together of people with diverse backgrounds, skills, and views.

Tuesday, November 4, 2025 at 6:38PM

Tuesday, November 4, 2025 at 6:38PM  science communication

science communication