ALBA-IBRO Diversity podcast

Thursday, June 19, 2025 at 3:35PM

Thursday, June 19, 2025 at 3:35PM  science careers

science careers Becoming a Scientist

Virus Fighter

Build a virus or fight a pandemic!

Maya's Marvellous Medicine

Battle Robots of the Blood

Just for Kids! All about Coronavirus

Thursday, June 19, 2025 at 3:35PM

Thursday, June 19, 2025 at 3:35PM  science careers

science careers  Thursday, June 19, 2025 at 3:32PM

Thursday, June 19, 2025 at 3:32PM

science careers

science careers  Thursday, February 6, 2025 at 8:59PM

Thursday, February 6, 2025 at 8:59PM

science careers

science careers  Monday, November 18, 2024 at 10:35AM

Monday, November 18, 2024 at 10:35AM  science careers

science careers  Sunday, October 20, 2024 at 4:30PM

Sunday, October 20, 2024 at 4:30PM From an interview with Superbugs

I didn’t really know what a scientist was growing up in Australia. My Dad was a truck driver, and everyone around me either drove trucks or worked in factories. If it wasn’t for watching nature documentaries on the TV, I probably would have dropped out of high school and become a truck driver too. Listening to David Attenborough explain how life was interconnected changed my pathway in life. I had a taste of wondering “why” and hearing it explained, and I wanted to know how the how world worked.

I got good grades in school and went to university. Although, to be honest, you didn’t need especially good grades to get into a science degree – it is rather inclusive entry, unlike medicine or engineering which are tougher to get into. I’m also not especially convinced that the grades you get during your degree in science reflect much about your capacity to be a scientist. The undergraduate degree has to give you the baseline of facts and tools, but once you graduate and become a scientist you are operating at the very boundary of human knowledge. It doesn’t matter if you are quick or slow, have a photographic memory or need to look up basic formulas each time. Science is different from any other walk in life. You can fail and fail and fail, but by succeeding just once you add something new to the sum total of humanity’s knowledge. When I think about what it takes to succeed as a scientist I think it really comes down to three things: creativity, resilience and integrity.

Why creativity, resilience and integrity? Creativity because we don’t know what the right experiments are. Once you are at the boundaries of knowledge, all you can do is take an educated guess, design the best experiment you can, and see if it sheds new light. Most of the time it doesn’t! So a creative scientist is someone who is good at coming up with multiple different ways to attack a problem. Of course, this means a lot of failure, which is where resilience comes in. Failing multiple times is a serious downer. Classical high achievers often struggle when they transition from acing every exam to failing in the lab. If you’ve got grit, if you know how to pick yourself up and try again, then you’ll eventually solve the problem. That is what science is, being wrong over and over again, until in the end you are right. Finally, integrity is key. You’ve just got to be honest in science. To make progress we need to build a tower out of data. People who are willing to fudge their results, fool themselves into thinking they are right when they are not, they start building their tower on poor foundations. The scientists who are willing to admit they are wrong, change their mind with new data, and take the slow route are the ones who end up building the highest.

I guess this doesn’t make science sound super attractive as a career! It is genuinely hard, and few people actually enjoy being wrong over and over again! But the thing is, when you are right, it is amazing. When we find something out it is actually something entire new that we have created – we have moved the sphere of human knowledge further out. There are also a lot of perks to a career in science – I get to travel a lot, don’t need to wear a suit, and the work is easier and for more money than driving a truck or working in a factory!

For myself, after a research career in Australia and America, I started to become more interested in creating a space for scientists to excel in, rather than doing science myself. I moved to Belgium and set up a lab in a hospital there. I tried to bring in a team of amazing people with different skills and backgrounds – biologists, mathematicians, clinicians, engineers, chemists and more, precisely because we never really know the best way to tackle the new problem. My job is to pick the questions we work on, and help the team to find ways to put together their skills to answer those questions. By having a team of diverse people who think in different ways we became much more successful at finding a winning formula. We have uncovered the causes of human diseases, solved riddles for why some patients are sick, started clinical trials that brought new treatments to neglected patients, even developed new drugs. Each success we have opens up a new and more interesting problem, and we are genuinely improving the world.

After a decade in Belgium I moved over my lab to Cambridge. We are still working on interesting problems in pathology, and I still have an amazing team of diverse scientists. Perhaps the best part, though, is that so many people have left my lab and have started up their own teams, in universities, hospitals and biotech companies, all across the world. That decision I made to go into science after high school has led to hundreds of scientists being trained, and humanity will build on the knowledge they create long after I am gone.

Monday, September 30, 2024 at 11:35AM

Monday, September 30, 2024 at 11:35AM Who or what called you to lead?

My journey into leadership started with a deep-rooted desire to care for others, a calling that was shaped by my childhood experiences. Growing up in foster care, I spent a lot of time with my grandmother, who was a kind and caring person. She didn't just take care of me—she took care of everyone around her. Watching her selflessness made me realise early on that I wanted to follow in her footsteps and help people.

At 15, I ran away from home and started working in healthcare. My first jobs were in hospitals and nursing homes, and by my early 20s, I decided to go back to school to become either a paramedic or physician. However, my path took a major turn after I was in a serious car accident, which left me in rehab for two years. The physical toll it took on me made me question whether I could handle the intensity of working in the ER, something my mentor—who had become a close friend—strongly advised me to reconsider.

After another accident in the ER, I realized that my body simply couldn’t endure the demands of the job. So, I shifted my focus to research, with the help of that same mentor who pointed me towards a biotech research program. I was working in immunology at the time, but it wasn’t long before neurology caught my attention. Years later, I crossed into that field after meeting my co-founder, Adrian Liston, when he set up his lab in Belgium.

Adrian’s brother tragically passed away from a traumatic brain injury (TBI), which deeply impacted both of us. That loss shifted our focus toward the huge unmet need for TBI treatments. We started applying the immunological research I had been working on toward neurological solutions, and what we discovered was promising. In transgenic animals, we were able to get effective immune responses in the brain. From there, we realised that with gene therapy, we might be able to translate these findings to humans and potentially save the lives of TBI patients in those critical early stages.

When Adrian moved the lab to the UK, we founded our company and have been dedicated ever since to making this a reality. As a leader, I’m driven by the desire to fill the gaps in healthcare, especially for conditions like TBI, where treatments are sorely lacking. My goal is to translate cutting-edge research into therapies that make a real difference for patients and their families.

science careers

science careers  Sunday, September 29, 2024 at 1:39PM

Sunday, September 29, 2024 at 1:39PM Stories of people's unconventional routes to becoming scientists are told in a new graphic novel intended to encourage others into the field.

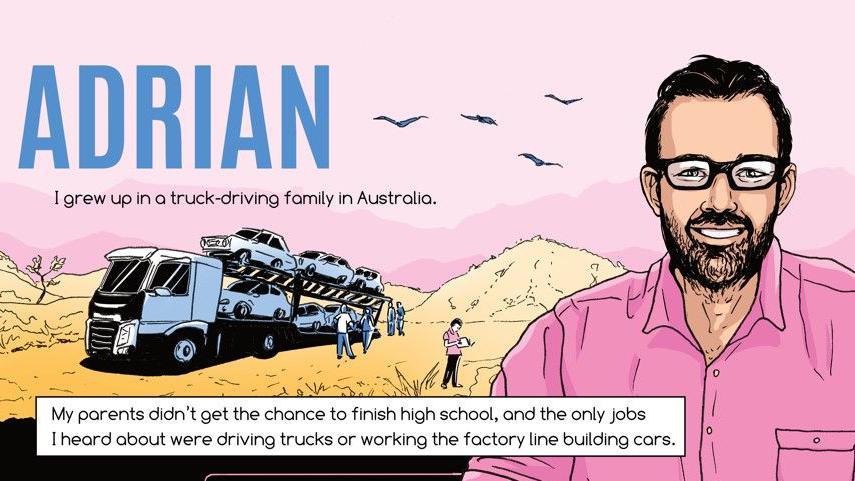

The book - Becoming a Scientist - is aimed at young adult readers and was written by the University of Cambridge's Prof Adrian Liston, and illustrated by Yulia Lapko - a business administrator for the pathology department.

Both their routes could be deemed unconventional as Prof Liston was expected to join his truck-driving family's business in Australia, while Ms Lapko fled her native Ukraine in 2022 following invasion.

Prof Liston said as a youngster he did not even know what a scientist was, and hoped the stories showed the "many different pathways".

The novel told the stories of 12 members of the Liston-Dooley lab, who researched the immune system and tissues during pathology.

This was not Prof Liston's first book and he has written books for young children including All about Coronavirus, Battle Robots of the Blood and Maya’s Marvellous Medicine.

His graphic novel, however, was aimed at older readers between 12 and 18 years of age.

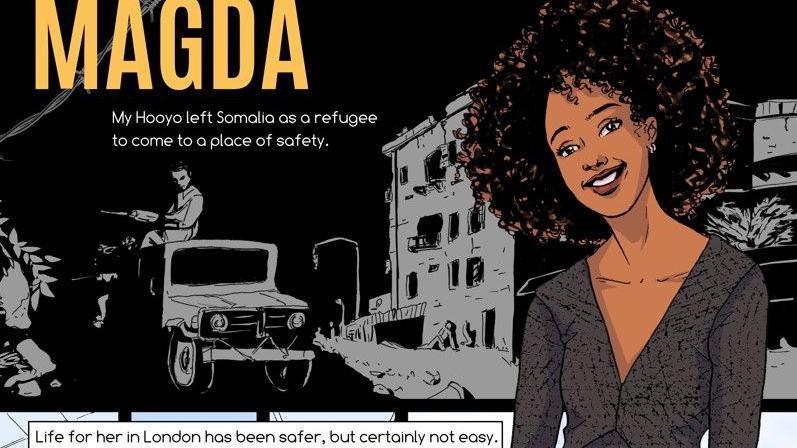

Stories about how the team members came to work in science are told in the graphic novel

"It was really luck more than anything else that allowed me to fall into the career I have today," Prof Liston said.

"When I looked around the amazing people in my lab, I realised that everyone had a story about overcoming barriers to enter science."

Magda Ali, Ntombizodwa Makuyana and Amy Dashwood became models for the cover of the book

Prof Liston freely admits he was not brought up to be a scientist.

In the book, he said: "I grew up in a truck-driving family in Australia.

"My parents didn't get the chance to finish high school and the only jobs I heard about were driving trucks or working the factory line building cars."

He added: "I never met a scientist. Actually, if I hadn't been inspired by the weekly nature documentary on TV I'd never have known being a scientist was possible."

Adrian Liston was inspired to follow a scientific education after watching nature programmes on television

Studying at university was "an epiphany for me", the professor said.

"Sure, there was class snobbery, but I was also able to find my group who were weird like me."

He told the BBC: "I want to see more kids with grit and creativity really look seriously at science as a potential career, and I realised that my team here at Cambridge really demonstrated just how diverse scientists are in practice.

"Every one had their own story of adversity conquered, their own role-models and their own motivations, so I thought we could simply tell their stories.

"While each one is unique, together they do show that science can be for anybody, and science becomes richer for having a diversity of talents."

Magda Ali pursued her education because she dreamt of becoming a scientist

Other stories included those of Magda Ali, who is completing her PhD at Cambridge University. Her parents came to the UK as refugees from Somalia and although she attended a school where few students even took A-levels, she continued her studies and her dream of becoming a scientist.

Visiting student researcher Alvaro Hernandez said he failed his school entrance tests in Peru at the age of five and almost did not get an education at all, having been preoccupied instead with football.

"I think my early teachers would be surprised to see me in Cambridge," he said in the book.

Their diverse stories have been illustrated by Yulia Lapko, who came to the UK under the Homes for Ukraine scheme.

Yulia Lapko came to the UK after her native Ukraine was invaded by Russia

She had been working as an artist before the war, but on arriving in Cambridge, and added: "I took a break from that because, settling in the new country, it made sense to get a full-time job for a sense of security and stability. Now that I feel settled enough I can expand the possibilities of what I can do with my skills.

"I really enjoy being here, I love the department and its people.

"Drawing people is my main speciality in art, and all the people featured in the book I actually see every day, which made it easier to capture them in a way that feels alive and effortless.

"But it’s one thing to see what people look like and the other is to really see them, to know the story behind each individual, so having all of them share their backgrounds, hopes and wishes really helped to get the whole picture of each character."

Prof Liston added: "It is guts and heart rather than brains that lead to scientific breakthroughs, and every discovery worth making happens from a team."

Read the book for free online or order a print copy.

Thursday, August 22, 2024 at 11:36AM

Thursday, August 22, 2024 at 11:36AM A Fellow of St Catharine’s has produced a new graphic novel to encourage high school students from all backgrounds to pursue STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics). Professor Adrian Liston (2023) has joined forces with illustrator Yulia Lapko on Becoming a Scientist: The Graphic Novel to tell the story of the twelve scientists in his biomedical research laboratory at the University of Cambridge.

Professor Liston explained, “Growing up, I didn't know what a career in science was. It was really luck more than anything else that allowed me to fall into the career I have today. When I looked around the amazing people in my lab, I realised that everyone had a story about overcoming barriers to enter science. While everyone's story is unique, what they have in common is inspiring – there are so many different pathways to success in science. I wrote this book to share these outstanding role-models with high school students, so they can find a story that resonates with them, and use that inspiration to go into STEM subjects.”

Cover of the Becoming a Scientist graphic novel by Prof. Adrian Liston with illustrator Yulia Lapko

Originally from Australia, Professor Liston is now Professor of Pathology at the University of Cambridge, a where he leads a team of researchers looking at the pathologies of the immune system. The idea for a graphic novel came about after Professor Liston’s group spent time at St Catharine’s for a team-building session, which invited each scientist to speak about their backgrounds, role models and motivations. With the group’s support, the new graphic novel devotes a section to each team-member’s story, with eye-catching illustrations provided by Yulia. Read the graphic novel online.

Detail about Prof. Liston's story from the Becoming a Scientist graphic novel

Yulia is an artist from Kyiv, Ukraine. She balances her art career with her day job as Business Administrator for Cambridge’s Department of Pathology.

She said, “I might not be a scientist, but I can relate to the idea that everyone has the potential to become anyone they want to be. Our paths might be very different, and some of them are longer and tougher than others, but the key thing is motivation. Relatable role models help nurture our potential, and I am excited that our book offers twelve role models to inspire young people.”

Becoming a Scientist is Professor Liston’s first publication for a young adult audience (readers between 12 and 18 years of age). He has previously written All about Coronavirus, Battle Robots of the Blood and Maya’s Marvellous Medicine for children between 3 and 8 years old, all illustrated by Dr Sonia Agüera González (also known as Tenmei).

Professor Liston added, “Some readers might associate graphic novels with fiction like Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman or Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s collaboration on V for Vendetta, but there is a rich tradition of creative biographical works such as Marjane Satrapi’s memoir, Perspolis, or Art Spiegelman’s interviews with his father in Maus.

“I am privileged to go to work every day with such a talented group of people and it has been an honour to tell the different stories that brought us all together in Cambridge. I hope these diverse experiences connect with and inspire the next generation of scientists.”

Some of the scientists featured in the graphic novel with Prof Liston (centre top row) in their lab (credit: Natalie Sloan-Glasberg)

The graphic novel is also available in print from https://www.thegreatbritishbookshop.co.uk/products/becoming-a-scientist

Wednesday, August 21, 2024 at 1:40PM

Wednesday, August 21, 2024 at 1:40PM Becoming a Scientist: The Graphic Novel is now available in print edition!