I just completed another "training the PhD supervisors" course, in anticipation of my first Cambridge PhD students. I have a few thoughts on training supervisors, but first my credentials and context:

1. Unlike most science professors, I took formal training in higher education, through a two year part-time Graduate Certificate program, and have published on PhD training.

2. 26 PhD students as supervisor (16) or co-supervisor (10). Of these, 18 graduations, 6 students still in progress and 2 drop-outs. Some easy experiences, where the students flew though. Some wonderful experiences, where I really got to help the student grow and flourish. Some steep learning curves, where the student and I took longer to get it together, but ultimately we both learned from the experience and the student suceeded. Some nightmares, that had me on the edge of quitting and occasionally still give me insomnia. I am a better supervisor today than I was 10 years ago, and hopefully I will be a better PhD supervisor in 10 years than I am today.

3. I see the PhD as a program where you create the environment that gives the student the opportunity to grow. This is difficult, since it involves understanding the student and pushing them just the right amount to stimulate them without intimidating them. The PhD for me is a highly versatile program, and I am happy for it to steer towards many different outcomes based on what the student is aiming for (academia, industry, etc).

So, my thoughts on training programs for PhD supervisors

First, they are necessary. The messages end up being fairly simple. Remember your PhD student is a person as well as a student. Learn that your student has different needs and expectations that you did as a PhD student. Learn to listen to their expectations, learn to be explicit in your expectations, be prepared to discuss and compromise. Document and revisit discussions. Learn the boundaries of reasonable expectations on both sides. Learn when to bring in extra help, learn where that help can come from. While these messages are simple, for many PhD supervisors it will be the first time they've explicitly heard them, and often new supervisors rely excessively on the lessons of their own n=1 PhD.

This is the raison d'être of these training programs, and the central work is typically done well. There are several common failings, however:

1. Pedagogy has a teaching problem. Education is an advanced academic field, with a highly specialised language, just like other fields. Unfortunately, many education experts use this language when training PhD supervisors. It is a major turn-off, especially to STEM academics, where even common humanities terms can be opaque or even just mystifying. Most supervisors are going to get less than one undergrad credit worth of education training - the use of specialist language is unnecessary and a barrier to concept uptake. I fully acknowledge that STEM disciplines have the same language barrier. I hope that one day there is a concerted effort to bring knowledge from STEM into humanities - and at that point we will need to learn the language of humanities to effectively communicate. But during supervisor training the onus is clearly on the trainer to use discipline-neutral language.

2. Humanities and STEM are just too different. The PhD programs are so different, in style, outcome and supervision, that examples and advice end up being so generic it is of little value, or it jars completely with one of the fields. Just split up these training courses into humanities and STEM, replicate the common content and specialise the field-specific content.

3. Supervisor training programs are too reactionary. A common mistake for new supervisors is to focus on correcting problems that they experienced during their own PhD. It can result in them being blindsided by different challenges. Ironically, the very classes that teach this are often guilty of the same problem. These courses are designed around the failings of current senior faculty. It is almost "what do we wish our senior lecturers had been taught 20 years ago?" in content and context. In STEM, the biggest failure in the senior supervisor population is the "sink or swim" mentality, which essentially assumes that any student who struggles is not cut out for a PhD (i.e., the failure is entirely in the student). This is demonstrably incorrect and propogates major problems of inequality. However, while this flaw is common in senior supervisors, it is becoming extremely rare in junior supervisors. When given problem examples, junior supervisors tend to first assume the failures are entirely in the supervisor. I have seen more issues arise from junior supervisors trying to be a friend to their students, or over-committing their time to a single student, then I have from junior supervisors neglecting their students. This is not to say that neglect is not a problem - it is, and needs to be addressed. However training courses for junior supervisors should better reflect the problems that are common in junior supervisors.

4. Training programs are less valuable because they are siloed. This training is focused on the well-being of the student, and is essentially dedicated entirely to situations where the student has a problem that can be fixed by behaviour-change in the supervisor. We know, however, that junior faculty are under enormous stress, rife with anxiety. One of the biggest sources of stress can be the very rare cases of problem students. This situation, of a problem that requires behaviour-change in the student, is almost entirely neglected in supervisor training. We are trying to fix one side of the equation in this training, and the other side is often entirely neglected or dealt with in a generic "stress resilience" training course (which also assumes the flaw is in the faculty not being able to deal with the stress). What we need is integrated training. Pitch us the same problem scenario twice, but with different missing context. Walk through the problem scenario with missing context A, where you need to change. Walk through the problem scenario with missing context B, where the student needs to change. Discuss how to identify developing problems, how to reflect on whether you are dealing with a context A or context B issue, and what practical steps to take in each context. I really dislike the problem scenarios where we are expected to take a one paragraph description at face value - real lab problems are never that simple, and always involve looking at a problem from multiple perspectives. Real solutions always involve trade-offs. Let's not pretend to junior supervisors that they will be in a situation where they can just invest limitless time - there needs to be hard barriers to stop work-life imbalance on their side. Let's also not pretend that a supervisor-student relationship exists in isolation - it has impacts on the entire lab, and trade-offs are always required. Perhaps this comes from a STEM vs humanities divide, but I see the concept of the team/lab almost entirely neglected in problem scenarios and trouble-shooting.

Finally, a little self-reflection. I would give this particular training course a 9/10 - probably the best I've been through. And yet 90% of what I wrote is a criticism. Occupational hazard? I think in STEM we move very quickly on from the success to trying to fix the failures. I know that when I run evaluations I need to force myself to stop, and say "well done on X, Y and Z. These are important. Congratulations. Now let's talk about A, B and C, which need some improvement...... Again, well done on X, Y and Z."

Wednesday, October 7, 2020 at 1:59PM

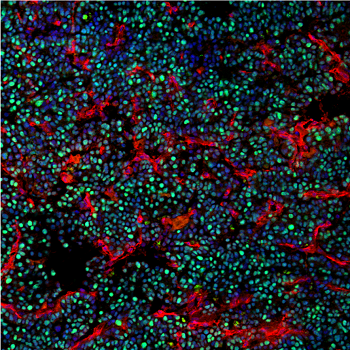

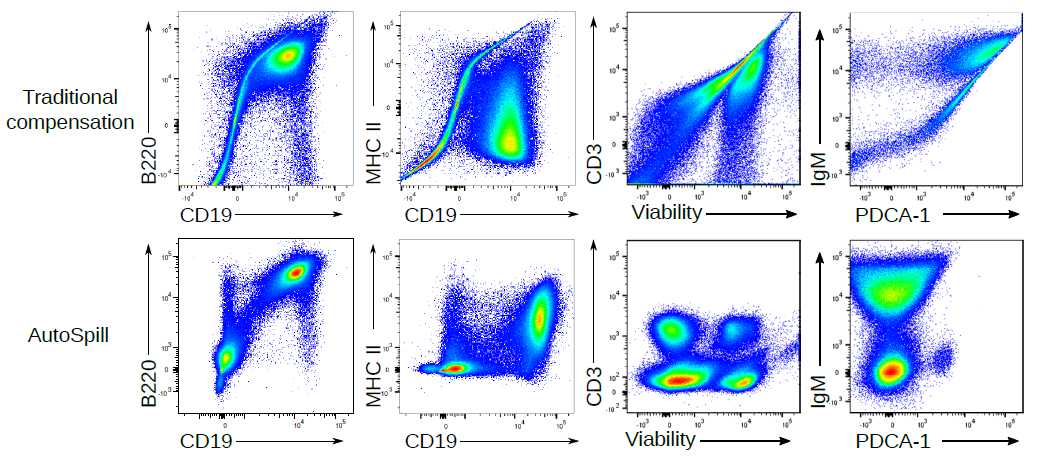

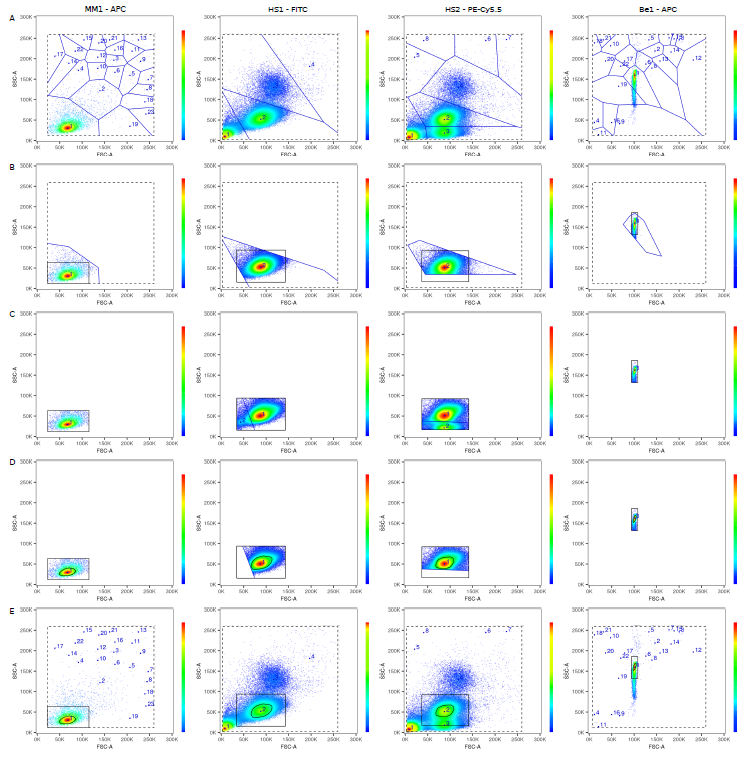

Wednesday, October 7, 2020 at 1:59PM  Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna have just won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. They have been my picks for the prize for years now. Nobel Prizes are often awarded decades after the fact, but CrispR has been such an obvious winner that it is a surprise it took until 2020 to be awarded. (Largely, I guess, due to the politics of several competing claims and patents, that have been going through the courts).

Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna have just won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry. They have been my picks for the prize for years now. Nobel Prizes are often awarded decades after the fact, but CrispR has been such an obvious winner that it is a surprise it took until 2020 to be awarded. (Largely, I guess, due to the politics of several competing claims and patents, that have been going through the courts).  genetics,

genetics,  immunology

immunology